My father belongs to the generation of men with self-imposed shyness. Not his fault, by the way. Men of his times (at least in my family) were archetypal providers with clearly defined gender roles. They earned, bought provisions from supermarkets or ration stores, vegetables from the vendors—by striking the best deals possible —, managed finances, took essential decisions and (here comes the most crucial competency) never betrayed their emotional side. Few could cook a meal; most of them had nothing to do with changing nappies.

Coming back to shyness, I am told that my father never played with me till I became 4 or 5. In the apartment-style dwelling where my grandparents lived, everyone knew everyone. The idea of a young father playing with his baby was uncommon and not yet popularised by advertising. It was considered frivolous and maybe not deemed manly. My mother tells me that when he held me for the first time, he joyfully said, ‘Mera beta school jayega’. His hard-earned degrees are his most prized possession. Naturally, he wanted me to have the best education. I do not have any memories of playing with him and till some time ago this used to rankle with me.

Whenever I think about academics, memories with my father zoom into a sharp focus. He loved showing me the North campus and all the pretentious DU colleges in an aspirational way. Walking by the campus, he would excitedly take me from one road to another, telling me about various colleges and faculties as well as the history behind them. He would proudly stand before Hansraj College (his alma mater) and DSE (Delhi School of Economics), fondly remembering his teachers, friends, and food vendors. By the time we grew up, we could accurately predict that DSE memories to be followed by encomiums on Manmohan Singh and Amartya Sen, who had taught his MA Eco. batch for a while. My dad is a very passionate sort of old man; when he talks, it seems his very being depends on the topic; as if he has spent 70 years ruminating on nothing else but that subject. In other words, he is a very engrossing speaker:)

The Trip that Happened

Some days ago, I was trying to retrieve a memory of us together, a time when he had dropped the academic cloak to show me something else. In the annals of my past, I was groping for some tender moments with him. After some conscious digging, a shadowy memory tumbled out: our visit to Purani Dilli to buy fireworks on Diwali. I must have been twelve or thirteen. Every year, he visited the various markets of old Delhi (Khari Baoli, Sadar Bazaar, Chandni Chowk etc.) all in a day to buy stuff for Diwali. These being wholesale markets, one could bargain an elephant for the price of a shrew. Irritatingly for my mom, he always chose Diwali day for his annual adventure. He got scolded by my grandmother, endured dagger looks from my mom, and yet, the braveheart chose to visit Purani Dilli when there was so much to do at home before the evening Puja.

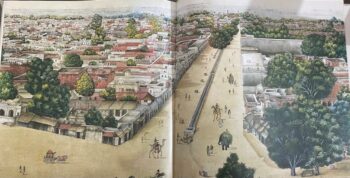

Sadar Bazaar was of particular interest to us as children, for that’s where our fireworks came from. One year my dad decided that I had grown up enough to accompany him on his Sinbad like wanderlust and thus we boarded a rickety DTC bus to Chandni Chowk. Thanks to his detailed narrations during numerous bus rides, my siblings and I knew all the significant landmarks by heart. Indira Gandhi Indoor Stadium followed by a long stretch of samadhis (Raj Ghat, Shanti Van, Shakti Sthal and all), the famous Irwin hospital, Daryaganj (marked by huge posters of certain ‘Sablok Clinic’), Jama Masjid on the left, Red Fort on the right and bang opposite the fort was the famous Chandni Chowk. We got down at Chandni Chowk in front of the Jain Chikitsalaya for birds. My father painted a surreal picture of what the market must have been in the Mughal era. ‘Imagine a market—not as crowded— with tree-lined wide roads and dotted with fountains. From the high courtyards of his palace, the king would have looked upon these streets on which we walk today. He would have admired the bustling market bathed in the cool moonlight. Therefore, Chandni Chowk.’ He meandered from one story to another while I listened enrapt. When he told me we were walking through one of Asia’s biggest markets, I strode on purposefully, hungry to explore more. ‘Look at the vendors. You’ll find everything here from clothes to household items, posters, paintings, old books, maybe even an aeroplane engine if you scrounge patiently,’ he winked at me.

(An artist’s (Mazhar Khan’s) view of Chandni Chowk in 1846. Image courtesy: Delhi 360°: J.P Lost)

Closer to Jama Masjid was a place called ‘chor bazaar’. I wondered how the authorities allowed a market that openly claimed to sell stolen stuff. But then the teenager in me was painfully discovering that the adult world was not what it pretended to be.

Dad pointed out the narrow ribbons of streets, a fully functioning network that old Delhi inhabitants are still accustomed to. Much later in life, I came to know how these streets had inspired Hindi /Urdu poet Gulzar to call them ‘बल्लीमारान के मोहल्ले की वो पेचीदा दलीलों की सी गलियाँ’ while he was writing an introduction to Mirza Ghalib’s biopic, which he also directed. Interestingly, Gulzar was inspired by the English poet T.S Eliot’s line (‘Streets that follow like a tedious argument of insidious intent, The love song of J. Alfred Prufrock)

I was told that when the day vendors left Chandni chowk in the evening, the market did not come to a standstill. In fact, new vendors replaced the old, and a shimmering night bazaar popped up like a mushroom at the same place. I was stepping into my dad’s world, feeling the rush you get on being invited into the domain of grown-ups. Holding my hand and attention, he was recounting tales while leading me into the space he had adored as a child.

Years ago, my granddad would have shown him that market in the same way. The crowd could have intimidated me; he replaced fear with interest and curiosity. We bought a few things for our house: posters of stonking villas with inspirational captions like ‘dream an impossible dream’, table covers, toys for my young brother, and other sundry items. In between, we passed by the Sheesh Ganj Gurudwara, where someone handed us a bowl of ghee dripping kadha prasad. Tired, we halted at a sweet shop to gorge on Rabdi Falooda. Every time dad served me an experience, he tried to gauge how impressed I was. ‘If you’re not scared of crowds, old Delhi will delight you at every step.’ I nodded in agreement.

After a long walk, we reached a place that seemed like a buzzing humanity hive. This was the famed ‘Sadar Bazaar’. My father lifted me on his shoulders as if to drive my excitement to a crescendo. ‘See, how crowded it is.’ He was quivering with delight even as I wondered how we would navigate through the crowd. But we managed just fine. There was a method to the madness. Everyone was there to buy or sell, and tacitly, people respected that pact. The place teemed with hawkers selling rockets, Laxmi bombs, charkhi, anar and other fireworks. Probably there were shops too, but I mostly remember the persistent hawkers lugging bags of fireworks. My dad haggled mercilessly. The hawker would say 80 Rs. for a packet of anar, to which my father would say ‘not a penny more than thirty.’ A bit embarrassed with this brutal attack on pricing, I would try to hide behind my father.

“Give him 40, papa,” I would say weakly.

“Stay quiet; you know nothing about the bargaining here. 30 is my last price.”

Dad would say conclusively and walk ahead in search of desperate sellers.

“Ok, take it.” I was shocked when the hawker called us back and sold his wares. Both my dad and he wished each other for Diwali. In an hour, we made quite a loot from Sadar bazaar. It had begun to get dark. We could hear the festival’s beginnings with fireworks bursting like constellations on the dark November sky. Loaded with treats for the entire family, we boarded the bus home. My first visit to the dusty, crowded old Delhi began as a love affair. I visited it several times later, undeterred by the crowd, chancing upon silver jewellery shops or an ornate cornice of a dilapidated ‘haveli’ hiding behind a maze of wires. Unwittingly, I have found myself pointing out the landmarks of Delhi, Hyderabad, Pune (three places where I have lived) to visitors with the same energy and romance that my father had invested during my first visit to Chandni Chowk.

That Diwali, when we opened our burgeoning cloth bags, I talked as much about the old Delhi markets as I did about the purchase we had got back home.

By the way, most of the fireworks we had bought that Diwali were duds. The seller had the last laugh after all.

“One has to be prepared for these things,” dad said prophetically. Life is a box of chocolates, Forrest…:) and you know the rest, don’t you? Next year, it was my sister’s turn to accompany dad.

Our mind has a strange way of focusing only on the negative. For some time, I had told myself the story that my father had not spent enough time with me as a child. Perhaps, he had not. He does not hail from the generation that could plan a vacation at the drop of a hat. Family and work were the pivots of their lives. How conveniently I had brushed aside the time he had spent solely with me. Trips to Connaught place bookstores to buy new copies of Penguin books in my undergrad curriculum, taking me to the PTI (Press Trust of India) canteen for a sumptuous dosa treat, taking a 14-day leave from his office to help me prepare for a Math compartment exam in grade IX. The visit to Chandni Chowk was gathering dust in some corner of my mind. I just needed to retrieve it like Aladdin’s lamp, rub it for some shine, and the magic happened!

Comments & Discussion

23 COMMENTS

Please login to read members' comments and participate in the discussion.