The mind is always active and moving, from one thought to another. The three broad themes are recalling the past, projecting into the future, or imagining a result. Such continual mental activity requires energy, and the mind does not seem to tire as long as we let it wander. Paradoxically, when we attempt to focus on something important such as studying for an exam, the same mind suddenly decides it does not have any energy.

Where is the disconnect? Can we summon the mind at will to work under our will and work as tirelessly as it does when it wanders from thought to thought?

The mind need not be a lifelong “wandering and chattering” companion. Mental energy is a great treasure. Although we cannot pinpoint the source of the mind’s energy, we can, by various methods, accumulate a critical amount of the mind’s energy, so we may overcome habits and reactions, keeping our attention wandering from thought to thought.

The field of the mind is infinite, just as the physical universe we perceive with our eyes. According to the well-accepted theory of the origin of the universe—The Big Bang—everything in the physical universe started as a point of infinitely great energy. Once the “Big Bang” happened, matter began to spread in all directions, and the universe continued to expand. At some point, when we first came to recognize our unique, individual identity, perhaps that was the moment when the mind began its expansion. Every day, we add more experiences and impressions to the mind, adding to the preexisting complex interconnections between thoughts.

Although the mind may continually be active, when we are asleep, there is no awareness of the mind. We can’t say with certainty that the mind disappears just because our awareness of the mind disappears. All our problems and worry seem to disappear into a big black hole. Yet, as soon as we awaken, the mind explodes into action. The same thought patterns, anxieties, worries, etc., come back, and the mind instantaneously expands to its prior conditioned state.

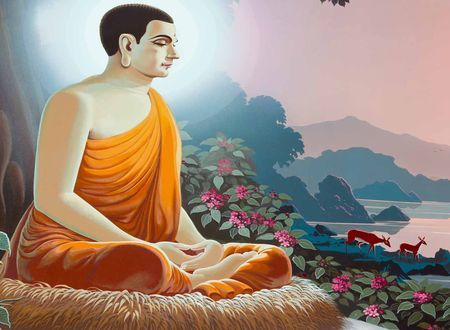

When we are engrossed in work, and that engagement is intense, we lose the sense of awareness of who we are and where we are. The mind’s energies crystallize into one place, and that mental focus does not get dissipated into extraneous thoughts. Despite our deep focus, we are generally not tired and may even feel refreshed. During such mental activities and in a deep sleep, we are free from the restlessness of the mind.

What if we could consciously pause, for a few minutes, the restless wandering of the mind? We would encounter a silent and thoughtless state. It is the same silent, thought-free state we were unaware of in a deep sleep.

In a silent, thoughtless mind, it seems logical that energy would be abundant. None of that energy gets dissipated in grooves of past conditioning as we perceive in the ordinary wandering and chattering state of mind.

The mind is too powerful for us to summon its energies at will and pause its activity. It won’t yield to any pressure or force, just as a fully grown tree trunk won’t budge even if we push against it with all our might. The roots of a fully grown tree are just too deep in the ground, holding firm and keeping the tree standing. Similarly, the mind has dug roots beyond what we perceive consciously, of thoughts and memories. Those roots form the foundations of the subconscious and unconscious minds. The more profound aspects of the mind we cannot consciously perceive are infinitely more extensive than the limited conscious arena where our attention wanders.

There is one thing our mind cannot control—our power to direct our energy of attention consciously. Imagine you are walking somewhere scenic, enjoying the surroundings and not paying attention to any one thing in particular. Attention gets diverted to many things in the vicinity, such as the path we may be walking on, trees, hills, a stream, etc. But everything changes if a mountain lion appears out of the bushes. Our conscious perception heightens, focusing on the object of danger. Everything else seems to disappear from our field of perception. Until the threat passes, we remain on high alert. Thoughts suddenly stop being a distraction, and nothing can break our concentration. Our lives depend on it.

Similarly, if we consider our power of attention as a precious gem and thoughts as dangerous thieves who come to steal it, we will likely closely guard our power of attention. Initially, it may take significant effort and willpower to keep our attention and focus under conscious control. As with most endeavors that get easier with time and practice, holding our focus and concentration relatively effortlessly for extended periods will also get more manageable.

One method of gaining more control over our attention and focus is taking advantage of the six to eight-hour rest that the mind and body get during sleep. Upon awakening in the morning, instead of letting our mind take our attention to yesterday’s problems, future worries, or the chores of the day, we can resolve to watch the mind. By watching and not participating, as the mind wakes up and unfolds the patterns, thoughts, and emotions it wants us to partake in, we create a separation between us and the mind.

For the first five minutes of the day, immediately upon waking up, think of yourself as an observer and not a participant in the activities of the mind. The inertia of the night’s rest will likely keep the mind relatively quiet. As we pry open a gap between our power to watch the mind and the contents of the mind, attention and focus integral to this process of watching strengthen. This exercise may help grow our power of concentration and focus without exerting force or pressure on the mind.

Comments & Discussion

1 COMMENTS

Please login to read members' comments and participate in the discussion.